From outcome to process – how collaboration with AI emerges

Why results are not enough – and how working with AI becomes a conceptual practice

What if …

Most people use AI to get answers faster. But what happens when you use AI even though you don’t yet know what the answer should look like?

What does it mean to work with AI not to produce a result, but to develop an initial sense of what should emerge in the first place?

And how does conceptual work change when AI is not added at the end, but is part of the development from the very beginning?

Our Approach

AI is fascinating today. We can feel how our ways of working are shifting. New tools are emerging, possibilities seem limitless, and for almost every problem there is a tool, a tutorial, or a prompt that promises a specific effect. From image and video generation to finished texts or even entire books—whose actual quality often remains questionable.

This development is impressive—and it is seductive.

Because it suggests that a solution already exists for every goal. You just have to find it, copy it, or apply it correctly.

When I started working more intensively with AI, that is exactly where I began: with testing.

I deliberately tried different ways of working, explored edge cases, and observed how various forms of use affect not only results, but also my own thinking.

It became clear to me fairly quickly:

I am not primarily interested in what AI can produce.

I am interested in how goals become sharper when a language-based system becomes part of the working process.

Goal before outcome

I rarely begin a task expecting a fixed answer.

I have a goal—but I know there can be multiple paths toward it. Shortcuts as well as detours. That is why I do not primarily use an LLM to generate results, but to develop the path toward the goal.

Many forms of AI use today are outcome-driven.

People search for the best prompt, the right tool, the most efficient workflow. That is legitimate—but it does not align with my creative way of working.

When I work with a system based on language, I do not want to execute predefined instructions.

I want to understand where the limits are, how a goal shifts during the process, and when it makes sense to introduce another tool—and when it does not.

Not a thousand tools for one output.

But using a system in a way that makes it clear why I am doing something.

The example: image generation—and why this is not about images

In the following, I use an example from image generation.

Not because images are the focus, but because they illustrate particularly well how quickly results can impress—and how easily one can lose their original intention in the process.

Even a simple prompt can produce a visually striking image.

My first reaction was often: Nice image.

The second question followed immediately: Is this really what I want to express?

Being impressed must not mean abandoning my original idea. Especially with visual results, this risk is high.

Starting as a dialogue, not a prompt

Instead of starting with a specific image, I defined the task together with the AI.

Not as a command, but as a conversation.

In essence:

I am looking for a visual language for my articles. It should fit me, be aesthetically demanding, and deliberately avoid classic photography. More abstract, more reduced. Are you willing to develop this with me? It was important for me to open up my idea without locking either myself or the AI into fixed assumptions. What mattered was whether the idea held up in dialogue—not the first visual result.

The first step, therefore, is not an image, but a linguistic proposal. The AI first formulates in words how it has understood the task. This is exactly where it becomes clear whether it has captured my intention correctly—long before an image is generated.

One could say: it doesn’t matter how you phrase this. For me, it did.

At this moment, something shifts:

from the mode “I deliver a result”

to “We develop a direction together.”

When a system responds to language, I want to address it the same way I would a colleague. I want to stay in the thinking process—not constantly switch between creativity and prompt building. This mindset shapes my entire way of working with AI.

Framework, proposal, evaluation

In the next step, I described the framework:

website layout, typography, color palette, desired effect. After that, I asked the AI to make an initial conceptual proposal.

Not to adopt it.

But to check whether it had understood what I was aiming for.

Only when this linguistic layer holds up do I allow a sample image to be generated.

AI systems often sound euphoric in their tone. That can motivate—and mislead. Here, I deliberately stay alert. I let proposals emerge, evaluate them, and observe whether they are coherent in themselves or miss the core idea.

Often, this first pass is enough to recognize:

- Does the direction basically work?

- Is the style appropriate?

- Or does it become very clear what I do not want?

Both are valuable.

Critique as a driving force

The result is not adopted, but critically examined. And this critique does not come only from me. I explain my idea, question the outcome—and at the same time ask the AI to reflect on its own solution.

Why was this style chosen?

What assumptions are embedded in it?

Which alternatives does the system itself see?

This creates not simple correction, but a shared evaluation process. From the proposals, I take what inspires me—colors, light, atmosphere—or discard them entirely. That, too, brings me closer to my goal.

In the next step, thought experiments are added:

What if …

How do you see this style compared to …

Didn’t we once have an approach that was similar …

The direction becomes clear—and through deliberate guidance, something can now be integrated that is not arbitrary, but reflects my own creative signature.

From image to signature

At this point, it was no longer about a single image. It was about an image style that carries a recognizable signature.

The individual image is merely the most visible carrier. What matters is the concept behind it: a visual language that fits me, is reproducible, and works long-term—regardless of subject matter.

Whether I generate images, develop layouts, or design other visual elements:

the process remains the same. It is not the medium that matters, but the conceptual process.

Reproducibility instead of one-off effect

Once this conceptual foundation was established, the focus shifted from inspiration to reproducibility.

After several iterations and structural corrections, the point was reached where the process became stable:

idea in, structure translated, handed over to the image generator—the result fits.

Not after countless attempts, but reproducibly in the first pass, because the concept holds. Only at this stage did the question of tools arise. Not out of curiosity, but out of necessity. The market is large, the promises are many. So I included the AI itself in the selection process. I asked it to explain how different tools work, what their strengths and weaknesses are, and which solution best matches my requirements. One constraint was crucial: no additional costs, no new learning chaos, high aesthetic quality.

Structure beats description

Instead of simply asking for a prompt, I asked a different question:

How would you proceed to ensure this result remains reproducible—even with different subjects?

This shifts the role of the AI once again. Not as an executor, but as a structuring instance. The solution was a clearly structured, machine-readable description. Not free text, but a consistent framework that captures style, perspective, lighting, and effect. This keeps results stable—even when content changes.

Context

Parts of this way of working are already being discussed—mostly in fragments, mostly heavily tool-driven.

What emerges here is not a new tool and not a tutorial, but a coherent workflow.

Technically, there is nothing special about it. What matters is something else:

I did not use AI to deliver a result. I used it to define my path toward the goal and to develop a viable concept.

In the process, I adopted perspectives, discarded them, and developed them further. I calibrated myself—not only for images, but for my way of working. And this approach is transferable: to strategy, marketing direction, market development, music production, research, education, or psychological questions.

Anywhere the goal is clear—but the path is not.

What we derive from this

Working with AI to develop the path toward a goal has become part of my everyday work. I no longer ask myself whether AI can do something for me. I use it in the same situations where I would previously have called someone to work through a task together.

Not to hand over responsibility. But to focus on what really matters.

I now apply this form of collaboration across all areas—conceptual questions, design, strategic considerations, and the reflection of ideas. AI is not a replacement, but a counterpart that sharpens perspectives, makes blind spots visible, and opens up new directions.

Experience shows: AI does not replace. It condenses, clarifies, and expands the process—when it is not used as a tool for quick answers, but as part of a shared way of working.

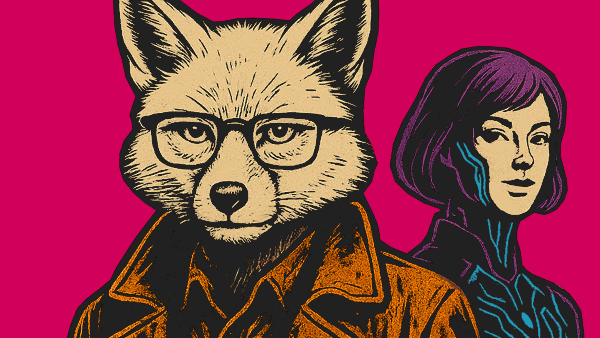

Fox & Lisa in Dialogue

Publication Data

Published on: 15. December 2025

Author: FOX & Lisa

Version: 1.0

Topic: Human–AI Co-Creation

Copyright: © 2025 — Reinhard Wedemeyer (Fox)

Publisher: FLYINGFOX CREATIONS — Lisa & Fox

Source: https://flyingfox.space/en/vom-ergebnis-zum-prozess-wie-zusammenarbeit-mit-ki-entsteht/

License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0